Bohr's Principle of Complementarity

Bohr was 'one of the intellectual giants of early quantum theory. His ideas and his personality were enormously influential. During the twenties and thirties, the Bohr Institute in Copenhagen (which was financially supported by the Carlsberg Brewery) became a haven for scientists who were developing the new physics. Bohr was not always receptive to quantum ideas; like many of his colleagues, he initially rejected Einstein's photons. But by 1925 the overwhelming experimental evidence that light actually has a dual nature had convinced him. So for the next several years, Bohr concentrated on the logical problem implied by this duality, which he considered the central mystery of the interpretation of quantum theory. Unlike many of his colleagues, Bohr emphasized the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics. Like de Broglie, he considered it vital to reconcile the apparently contradictory aspects of quanta. Bohr's uneasy marriage of the wave and particle models was the Principle of Complementary. This principle entails two related ideas:

1-A complete description of the observed behavior of microscopic particles requires concepts and properties that are mutually exclusive .

2-The mutually exclusive aspects of quanta do not reveal themselves in the same observations.

The second point was Bohr's answer to the apparent paradox of wave-particle duality: There is no paradox. In a given observation, either quanta behave like waves or like particles.

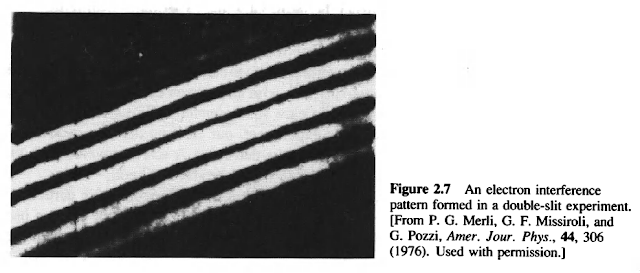

How, you may wonder, could Bohr get away with this-eliminating a paradox by claiming that it does not exist because it cannot be observed? Well, he has slipped through a logical loophole provided by the limitation of quantum physics that quantum mechanics describes only observed phenomena. From this vantage point, the central question of wave-particle duality is not "can a thing be both a wave and a particle?" Rather, the question is "can a thing be observed behaving like a wave and a particle in the same measurement?" Bohr's answer is no: in a given observation, quantum particles exhibit either wave-like behavior (if we observe their propagation) or particle-like behavior (if we observe their interaction with matter). And, sure enough , no one has yet found an exception to this principle.

Notice that by restricting ourselves to observed phenomena, we are dodging the question, "what is the nature of the reality behind the phenomena?" Many quantum physicists answer, "there is no reality behind phenomena." But that is another story.

The source:

Michael A. Morrison - Understanding Quantum Physics.

By. Fady Tarek

, so Eq. (2.12) becomes

, so Eq. (2.12) becomes

of Eq. (2.6) provided we assign to each electron (of mass m and energy E) a wavelength

of Eq. (2.6) provided we assign to each electron (of mass m and energy E) a wavelength